Creating Progress: John J. Kelly, Good Samaritan

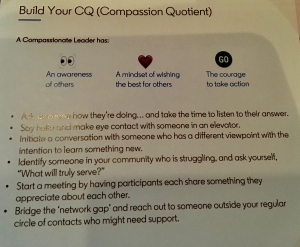

Our world needs kind leaders who create progress, and John J. Kelly was one such leader helping people improve their lives. The recently published book, The Quintessential Good Samaritan, tells of John Kelly’s life work in making a difference in the lives of so many people. Through many engaging stories we learn of his compassionate leadership style. What stood out in his leadership is humble connections with others, good story telling, and persistent pursuit of his ideals no matter the pushback. Over the course of his life, he did this as a priest, and educator, an advocate for the poor, a mentor for troubled youth, and an inspiration to the incarcerated.

Humble Connections

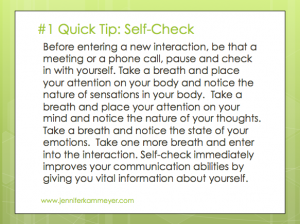

Time and time again, people recount how John Kelly met them as they were as an equal. He was able to erase the power gap of his position in society and truly connect human-to-human with others. One example of this connection was how at risk-youth went from making no eye contact and not speaking to calling John ‘abuelo’ (grandfather) and teasing him about his common expression ‘oh stop it’ as they laughed with him. A San Quentin inmate who built a strong relationship with John Kelly in his progress of turning his life from prisoner to positive community contributor in society, told of John’s connections to other as recounted in the book. “ . . . he was in his mid-seventies, yet he engaged nineteen and twenty-year old gang bangers – Noreños, Sereños, Black folks from the East Bay. You could look at him as a friend . . . He always came as an equal which attracted people to him.”

An important note is that John Kelly, because of his humble nature, would not take credit for all that I am attributing to him here or of the achievements listed in the book. He would attribute the success to the individuals changing their own lives and to the many citizens who contributed to building community and helping others. While all of this is true, his leadership did strongly influence change and progress in countless lives.

Stories for Wisdom

Storytelling was integral to John’s leadership. He told stories to illustrate life and he facilitated others to tell their stories both as a means of self-healing and as a means of sharing wisdom with others. He told stories as a priest to bring religion into the reality of people’s lives, as a teacher to demonstrate life lessons, and as a mentor to at-risk youth and the incarcerated to inspire. When John was mentoring at-risk youth, he had inmates from San Quentin write letters to the teens he was coaching and had them read the letters out loud to each other. They told stories of how they were once in the same place as these teens, thinking that the gangs were their families, only to realize that they would be abandoned when something went wrong and they too would end up in prison. The stories from people who walked the same path were so much more effective than a school guidance counselor lecturing a student about the hazards of gangs. And through the Kairos program at San Quentin, Kelly helped inmates change their lives with the important first step of writing their own stories to acknowledge both the tragedies of their childhoods and the responsibility of their own actions.

Passionate Persistence

Persistent pursuit of equal kindness and opportunity for all people did not make Kelly popular among some in power, but it did allow him to make the change he wanted to see in the world. As a priest, John Kelly pushed against what he believed was ill-guided in the establishment. He supported striking lay (non-priest) teachers who were not receiving commensurate pay to public school teachers, he permitted non-Catholics to participate in taking communion, and he deviated from traditional mass. All of these acts of defiance were motivated by compassion for people and the community. These acts had consequence both positive and negative. He made incredible human connections and life-time friendships and he also was chastised by the religious establishment and eventually left the priesthood. Yet his persistent pursuit of fairness continued through his work at Samaritan House and at San Quentin Prison. Many times, he bumped up against other leaders who believed he went too far in giving the disadvantaged second chances, even when they continued a life of crime. But those who managed to break the cycle would say that this unconditional love provided by Kelly was exactly what they needed to go against all odd to change their lives.

I was lucky enough to have met John Kelly on a few occasions, including when he spoke at San Francisco State University to a group of students interested in leadership and restorative justice. I saw firsthand his unrelenting passionate pursuit of ideals, his use of stories, and the human connection he so quickly created with the students. This student engagement was one more example of so many throughout John Kelly’s life where he instigated change for individuals and society.