Leadership titles line our bookshelf, but recently my husband, John Kammeyer, insisted that I immediately read Team of Teams by General Stanley McChrystal just as he finished it because the book was so insightful for him. After I read the book, our internal conversation inspired me to share John’s leadership perspective.

Why did you insist I read McChrystal’s Team of Teams right when you finished it?

I have read so many leadership books that focus on productivity or ‘hacks’ to accomplish more in less time. What I like about this book is that it explains why the processes we have been using for the last hundred years — originating from Taylor’s 1911 principles of scientific management — don’t currently serve organizations well. It recommends that instead of striving for efficiency, organizations shift to adaptively solving complex problems.

What is the core concept of Team of Teams?

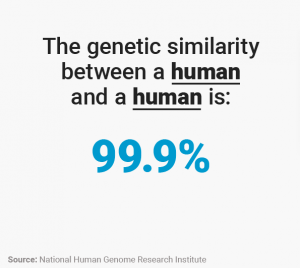

McChrystal proposes a new way to solve problems by breaking down silos and unifying different parts of an organization through extremely transparent communication and decentralized decision making. For McChrystal, this method shifted the way the United States addressed the dynamic threat in Iraq by unifying different elements from special operation forces to the CIA. The core concept is that in our information-heavy, ever-changing world, being adaptive must be valued at the same level as being proficient for organizations. To be adaptive, all teams must understand and be working toward the larger organizational goal and communicate with every other team. This makes a Team of Teams.

You have an academic understanding of leadership with a Master’s degree in Organizational Leadership, leadership experience as a Fire Chief, and now lead Training in a humanitarian rescue organization. Why is this Team of Team concept appealing to you?

It addresses a problem I see of leaders, including myself, struggling to apply traditional methods in a world becoming increasingly complex. Complex is different from complicated. Complicated can be difficult, but also predictable, so the Taylorism organizational principles of the 20thcentury worked well to solve the problems in the industrial and early informational ages.

“Things that are complicated may have many parts, but those parts are joined, one to the next, in relatively simple ways…they ultimately can be broken down into a series of neat and tidy deterministic relationships… Complexity, on the other hand, occurs when the number of interactions between components increases dramatically; this is where things quickly become unpredictable.”

The information revolution and current speed of technological innovation has moved the world from complicated to complex. Access to information has changed not only what we know, but how the whole world acts, increasing dependencies between moving parts and making prediction near impossible.

That is why there is a need to change the functioning of organizations away from optimizing process to being adaptable. I saw this increasingly in the fire service and now in humanitarian aid. Being adaptable means that every individual needs autonomous decision making at some level, and the only way that works is if they have the right information to make a decision that best serves the organization. The Team of Teams’ leadership facilitates both the distribution of information and a sense of camaraderie among members in an organization so that every function is working toward the same broad goal and can quickly adapt as unpredictable environmental elements change. These environmental elements change more quickly in organizations that are focused on crisis, such as the military and emergency services, but they are changing quickly in most organizations. And recently the pandemic and civil unrest in the U.S. has created unpredictable factors for every organization.

‘Shared consciousness for empowered execution’ is a key Team of Teams concept. What does that mean in practice?

In a word it means trust, organizational trust. Most of us are wired to be competitive or accomplishment-based and, because those two terms are usually measured against other people, it can create an unhealthy environment or organization. ‘Shared consciousness and empowered execution’ in practice mean that organizational objectives are known throughout and everyone feels they are contributing to those objectives.

One of my favorite stories in the book is about the janitor who works at NASA who, when asked what his job is, said, “to put a man on the moon.” I think that kind of shared consciousness and empowered execution requires a lot of trust throughout the organization and acceptance that everybody has their unique role within it. The idea is to be competitive to the problem not each other. What McChrystal makes clear is that shared consciousness must come before empowered execution. Prematurely giving autonomous decision-making power can lead to undesirable results where people and teams are doing things in their own best interest and not the interest of the full organization.

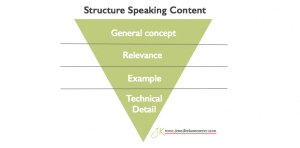

As you know, my greatest area of interest in all subjects is communication. What is the communication role of a leader in this method and why does it matter?

First and foremost it’s important to understand how change happens within an organization and how communication plays such a critical role. It’s easy to read a book likeTeam of Teams and want to go and change the world or maybe just your own small piece of the world, but change takes time and consistency. Communication is really the key to this change. Of particular importance is communication in the form of widespread sharing of organizational objectives and clear setting of individual and small group expectations. The responsibility for all of this falls on leaders at every level, and my experience has been that good communication about objectives and expectations decreases anxiety among teams.

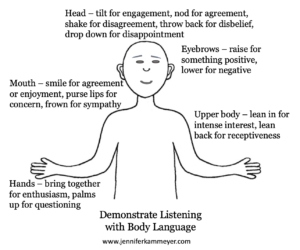

To put a fine point on it, people often confuse leadership communication with talking but really, it’s more about listening. In my last few years as fire chief I knew a meeting with my staff was successful when I emerged from the meeting having said very little and learned a lot through listening. In the Team of Teams method, leaders of all teams and the top leader need to actively listen to others in order to gain the information needed to make strategic decisions about what to do next.

What benefits are derived from this organizational leadership method?

A key benefit from this method is looking at problems differently, bringing in more information from many different areas of the organization to get a bigger picture and gauge all of the influencing factors. This has become more common with increased access to more data, but data in itself isn’t actionable. What is also needed is the connections within the organization to understand multiple changing factors of influence and potential outcomes in an uncertain environment. The term ‘mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive (MECE)’ is one McChrystal uses to describe the old way of using information when things were complicated, but gathering enough information allowed predictable outcomes. Those days are no longer, so the massive amount of information gathered needs to be paired with this intense interorganizational connection – shared consciousness.

Why is micromanaging counterproductive?

Often people think of leadership in an egocentric perspective of how their own leadership qualities or abilities affect the organization, rather than how the whole organization is functioning with many different leadership elements. Micromanaging is a top-down leadership problem that occurs in the leader who doesn’t feel confident or doesn’t understand their purpose of motivating and enabling others. Ultimately, micromanagement is counterproductive because people in the organization become disenfranchised when they don’t see how they are contributing unique value.

“ …containing my desire to micromanage, I flipped a switch in my subordinates …they acquired gravitas that they had not had before . . . Empowerment did not always take the form of overt delegation; more often, my self-confident subordinates would make decisions, many far above their pay grade, and simply inform me.”

Top of mind for so many leaders is greater organizational inclusivity. How do you see Team of Teams helping with inclusivity?

The Team of Team concept is designed to have everyone contribute value, so in that way it is inclusive. As I mentioned earlier, everyone in the organization should understand the overall objectives and I think it’s important to be able to talk through a problem involving a wide range of solutions. When many different voices and perspectives are heard, more options become available. Part of inclusivity is also transparency of information so that everyone has what they need to benefit the organization.

When should leaders consider using Team of Teams for their organization?

When an organization has complex problems with multiple disciplines, it would be wise to implement a Team of Teams approach in which you start to bring disparate disciplines together and shared perspectives begin to occur. I’ll go back to the difference between complex and complicated; a complex problem is non-linear and multi-modal. When you’re chasing down solutions to nonlinear problems and you have multiple disciplines across your organization, these are your Team of Teams. In the fire service this may mean fire fighting crews and emergency rescue crews; in business, product development and sales; and in humanitarian aid, rescue and resilience teams. In each case the success of the full organization is dependent on the interconnectedness of teams functioning in an ever-changing environment.

How can leaders get started in implementing this method?

Understanding the needs of your organization requires you to listen, gather information, distill that information, feed it back to your teams, and collaboratively determine a productive way forward. Then repeat, and repeat again.

“I needed to shift my focus from moving pieces on the board to shaping the ecosystem.”

A word of caution, though: There is a natural tendency to learn a new method of leadership and look at it as an easy fix. That attitude is what McChrystal calls a LIMFAC or limiting factor. This isn’t easy! It requires you as a leader to step out of the way of your teams, breaking old habits of controlling what happens, and it takes patience in difficult times. This attitude of leadership requires using your head for business and your heart for people – and always keeping the organizational mission as top priority. When organizational values are properly established and everyone is collectively cared for and understands their contribution, then each person and function can participate as a Team of Teams.

John Kammeyer was Fire Chief at Central County Fire Department for the last five of his thirty-year career in public service. He also served in the United States Coast Guard as a Rescue Swimmer, receiving the Presidential Commendation Award for a harrowing rescue. John is currently leading the training effort at a rapid-response humanitarian organization and continues his competitive athletic pursuits.