Zoom Fatigue Solutions

Move. Look up. Focus. Acknowledge Effort. Vary Medium.

Research on videoconference is rolling in from academics now that a year has passed since it became our primary means of communicating. While we’ve all learned the skills needed to do Zoom right, we now need to learn how to keep it from making us crazy. The latest research out of Stanford and San Francisco State University clearly shows that the fatigue we are feeling is real, with distinct causes, but also that there are ways to mitigate the problem. To tell just how much we are affected, we can take the ZEF Scale survey and contribute to Stanford’s research efforts.

Why the Fatigue?

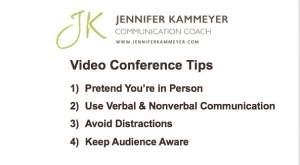

Based on the current research, the reasons we are feeling this Zoom fatigue – which is not specific to Zoom itself but to any videoconference platform – are both physical and psychological. Physically, we are not moving our bodies and our eyes as we typically do when we are meeting in person or talking on the phone. Psychologically, we are dealing with watching ourselves in action and with having to process nonverbal communication that is more difficult to catch and interpret.

When we don’t move our bodies, we fall into sitting-and-watching-mode where we become conditioned not to act and we have reduced subjective energy. When our eyes are fixed on one thing (the screen) for a long time, certain eye muscles stay in a tight position. This is in contrast to when we look at different things, as we do when meeting in person, and different muscles in the eyes contract and then relax.

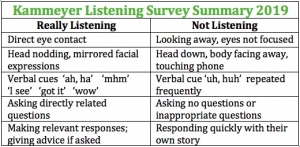

Psychologically, when we look at ourselves, we tend to be critical and that puts us into negative emotional states. There has never been a historical time when humans watch themselves while communicating the way we tend to do on videoconference right now. Another historical change is interpreting nonverbal communication when it is mediated through videoconference. In person, we are constantly picking up cues subconsciously decoding messages and making meaning from them. Not only is it harder to give and receiving nonverbal cues, but we are getting false cues that we need to interpret. This places a higher cognitive load on us. So, while we sit still, look in one place, see ourselves constantly, and work to send and interpret nonverbal cues, we are getting exhausted!

That is the bad news. The good news is that the research also gives us relatively easy fixes to these problems. We can move our bodies and our eyes, stop looking at ourselves, focus our attention, increase nonverbal cues given and interpreted, and utilize multiple communication media.

Move

Move it or lose it. Sitting all day is bad for us physically and psychologically, so we just need to move our bodies more. We can shift positions from a chair to a stool to standing for different videoconferences throughout the day. We can take short breaks by scheduling the start of meetings at five minutes past the hour; do burpees or dance to energetic music for three minutes in between meetings.

Look up

Avoid staring at one spot of the screen for a long period of time to eliminate eye fatigue. First take the opportunity to shift from looking at the speaker to the presentation materials, which are ideally on a separate monitor. We can position our computers in front of a window and look up right over the edge of camera to something far in the distance outside the window and then back again to move our eyes without appearing to be distracted. We can avoid watching ourselves and triggering negative emotional states by checking our frame when we start and then turning off our self-view.

Focus

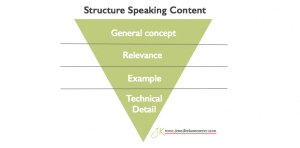

To avoid the drop in energy from falling into sitting and watching mode, stay with the flow of the meeting and avoid attempting to multitask (which is usually just task switching). Taking notes on paper (or even doodling) and responding in chat or with emoji reactions helps sustain on-topic attention. Setting the corporate culture to eliminate unnecessary meetings and making sure only those essential to the purpose attend helps to avoid people sitting on videoconference while doing other work.

Acknowledge Effort

Nonverbal communication mediated through videoconference simply takes more energy. We need to exaggerate our facial expressions and nod more in order for others to be able to read our nonverbal cues. We also carry a heavier cognitive load to interpret others’ cues. Did they glance to the side because they don’t understand or don’t believe us? Or did someone just enter the room on that side? We can ask more questions and engage people through chat, turn taking, and requests for reactions so that we are getting more feedback – but all that takes effort too. Acknowledging that effort helps us plan our workload more effectively. We can also specify when video is needed for a meeting, or at what points during a meeting, and when it is not. This works well for my students when online learning; we are on video when interacting and then off video when I present material and ask for written responses.

Vary Medium

All Zoom all the time just doesn’t work. It is like sitting in the conference room all day in meetings and never going back to your desk to get work done. Before the pandemic videoconference craze, we were more varied in communication mediums. As we come out of the pandemic, we will make choices about how we communicate from a wider variety of options. The best time to use videoconference will be when we cannot be physically in one place, but definitely need to see others.

With many of us still working from home, and with conversations starting about what post-pandemic office life will look like, it is helpful to have new research to guide us in using videoconference as an integral part of our daily work life. With making a few adjustments, we can keep being effective collaborators and communicators without exhausting ourselves.